Higher Education Finance

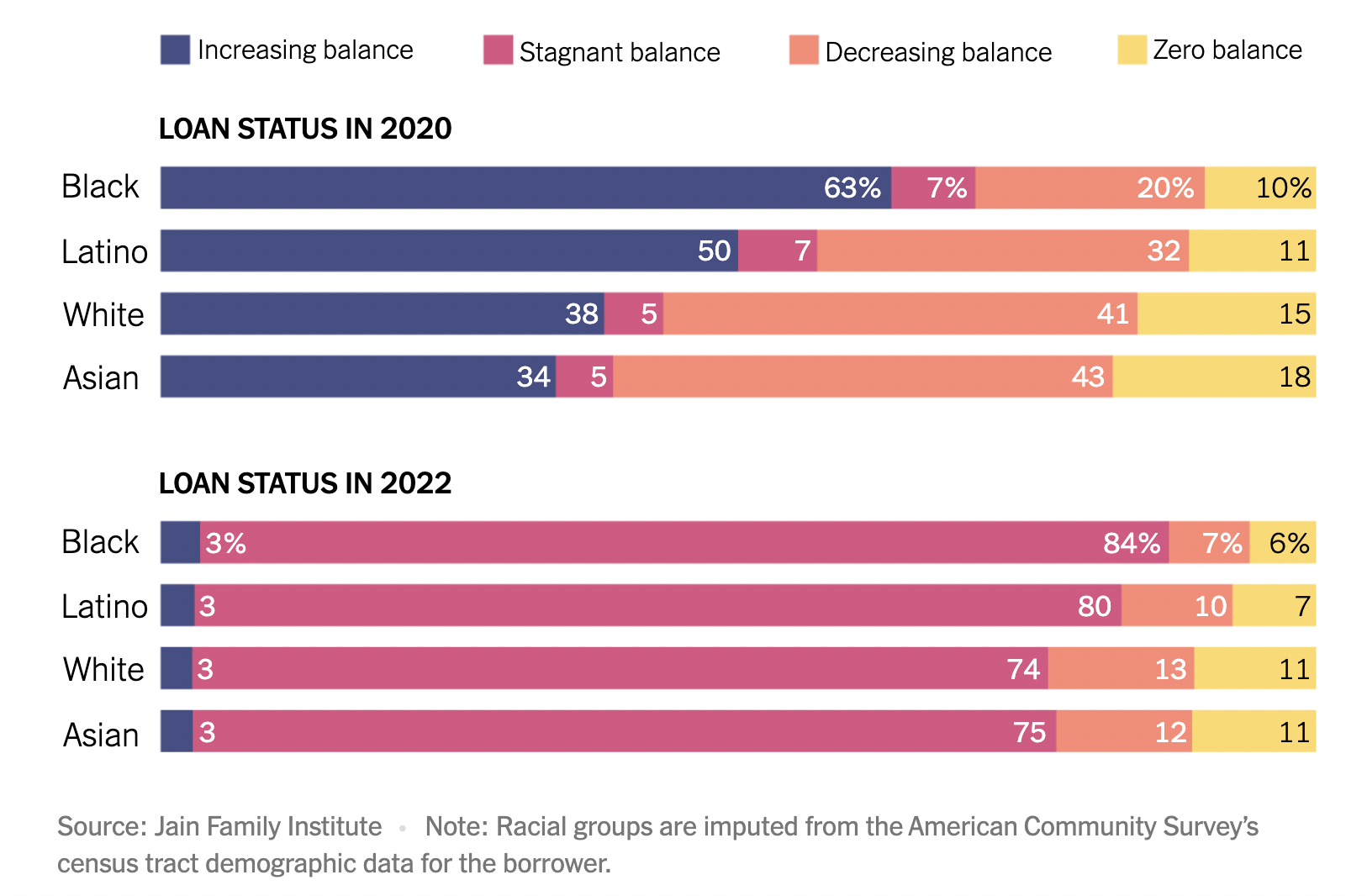

The American higher education system is afflicted by a crisis of quality, affordability, and access that belies its role in building an equitable and just society. This has found most pernicious expression in the mounting problem of student debt, a $1.7 trillion burden affecting over 42 million people. This burden often now extends to students’ families, and is disproportionately shouldered by historically marginalized groups. Absent any meaningful constraint on college costs, the student debt trap risks putting higher education – and its promise of economic mobility – out of reach for ordinary and low-income Americans.

JFI approaches the problem of higher education finance in two principal ways. First, we analyze interlinked, nationally-representative datasets to offer a detailed picture of student debt, examining race, ethnicity and class intersections, labor markets, and the impacts of institution type and geographic concentration. With this analysis, we identify high-impact policy interventions to address the existing debt burden and the broader affordability crisis. Second, we design, consult on, and produce research on income-contingent financing, an alternative to traditional student loans under which students pledge a percent of their income over a limited period. Designed with adequate safeguards, income-contingent financing reduces students’ risk by ensuring their payments never exceed their ability to pay.

PARTNER WITH US

We welcome academic and philanthropic partners interested in using our student debt data for collaborative or independent research. We have collaborated with educational institutions, scholarship funds (notably, the Student Freedom Initiative), workforce development agencies, and a range of investors on income contingent finance pilots, and we welcome further inquiries. We also provide analytics, evaluation, and design consulting for existing providers in order to ensure equitable, transparent and accountable financing.

PARTNERS

Featured Partners

Higher Education Finance Contributors

Eduard Nilaj

Data Science Research Associate

Ege Aksu

Fellow

Francis Tseng

Lead Independent Researcher

Laura Beamer

Lead Researcher

Marshall Steinbaum

Senior Fellow

Roberta Costa

Research Manager

Sérgio Pinto

Fellow

Sidhya Balakrishnan

Director of Research

Yunjie Xie

Fellow

Related Publication Series

Millennial Student Debt

Recent Updates

ISA research cited by White House and others

This research formed part of a White House issue brief, "The Economics of Administration Action on Student Debt."

Working Paper — Navigating Higher Education Insurance: An Experimental Study on Demand and Adverse Selection

A survey-based experiment in collaboration with the Philadelphia Federal Reserve.

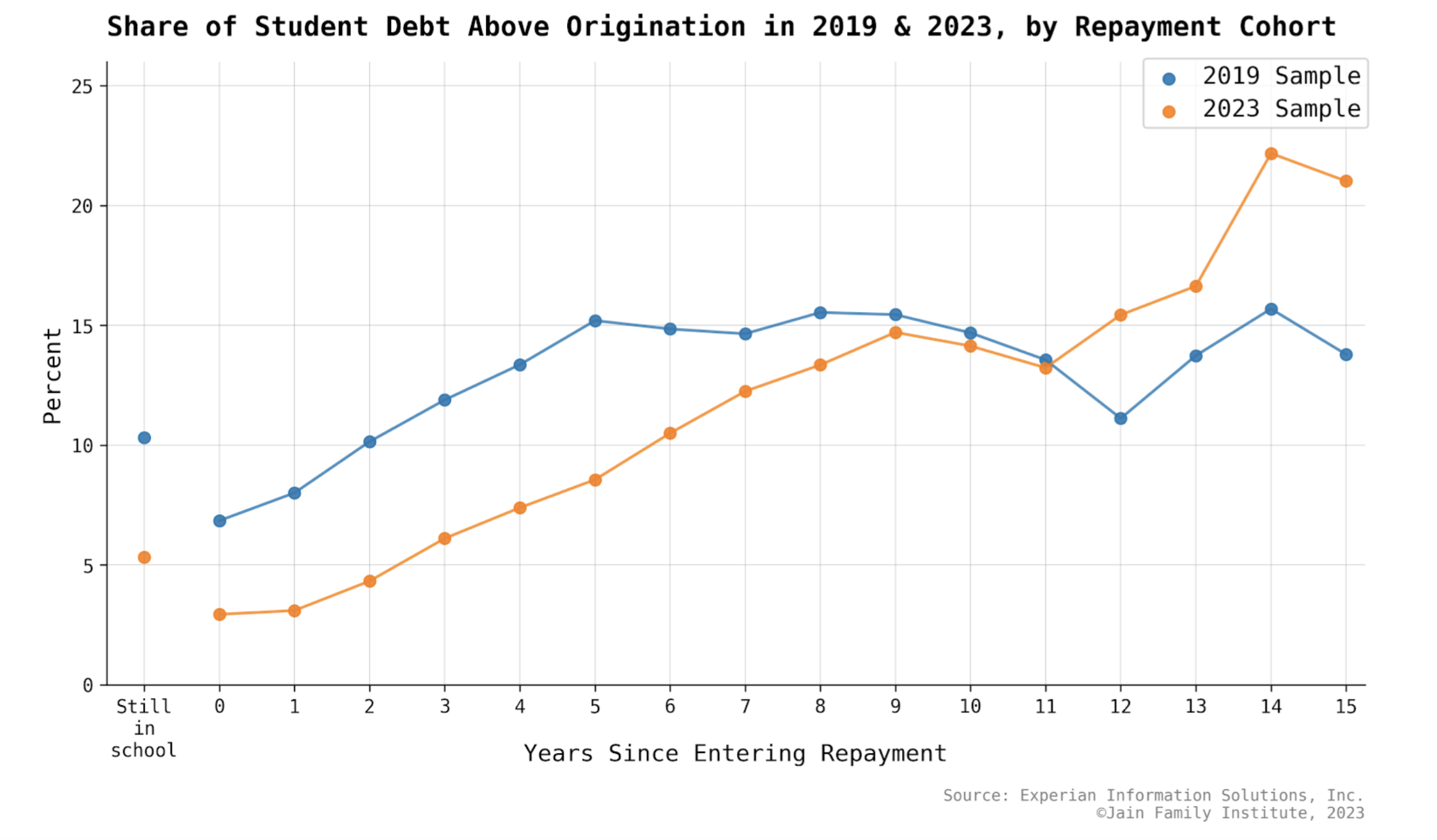

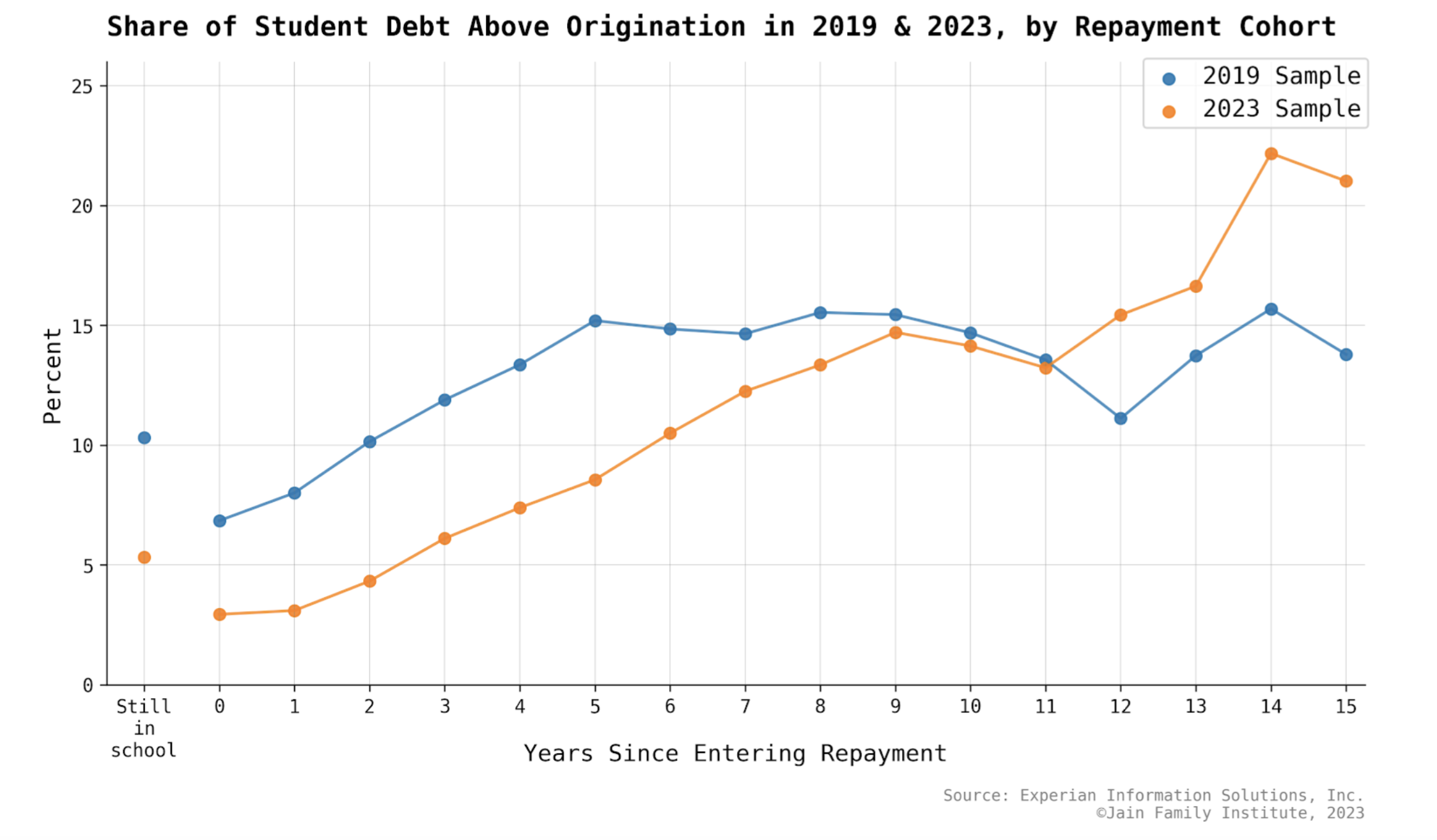

New Research in Millennial Student Debt: Relief for Borrowers with Negative Amortization

JFI's Higher Education Finance team publishes the first installment of part 14 of their flagship Millennial Student Debt research series.

Student Debt Relief for Borrowers with Negative Amortization

The first installment of Part 14 in the Millennial Student Debt Series, this report analyzes systemic issues in student debt non-repayment...

Part of the series Millennial Student Debt

Press Release: Student Debt and Homeownership Barriers in Washington, D.C.

A new collaborative report from the Jain Family Institute (JFI) and the Economic Policy Institute (EPI) sheds light on the...

Student Debt and Homeownership Barriers in Washington, D.C.

Part 13 in the Millennial Student Debt Series, this collaborative report sheds light on the intertwined challenges of student loan debt...

Part of the series Millennial Student Debt

Laura Beamer and Marshall Steinbaum publish editorial in the New York Times

"America's Student Loans Were Never Going to Be Repaid."

JFI’s Higher Education Finance research in The Guardian

Eduard Nilaj spoke to the Guardian after the Supreme Court's ruling against debt cancellation.

JFI’s Millennial Student Debt work widely covered in media

In light of a Supreme Court decision and the end of the repayment moratorium, coverage in Boston Globe, Forbes, Al-Jazeera,...

Fortune covers Millennial Student Debt research

On the resumption of federal student loan payments in October.

The New York Times covers JFI’s latest Millennial Student Debt report

On the upcoming end of a pandemic-era policy that has greatly benefitted student borrowers: the student loan repayment pause.

New Research in Millennial Student Debt: The Repayment Pause and the Continuing Crisis of Non-Repayment

JFI's Higher Education Finance team finds striking positive effects of the pandemic-era student loan repayment pause.

The Repayment Pause and the Continuing Crisis of Non-Repayment

Part 12 in the Millennial Student Debt Series, this report analyzes student loan repayment during the pandemic repayment moratorium.

Part of the series Millennial Student Debt

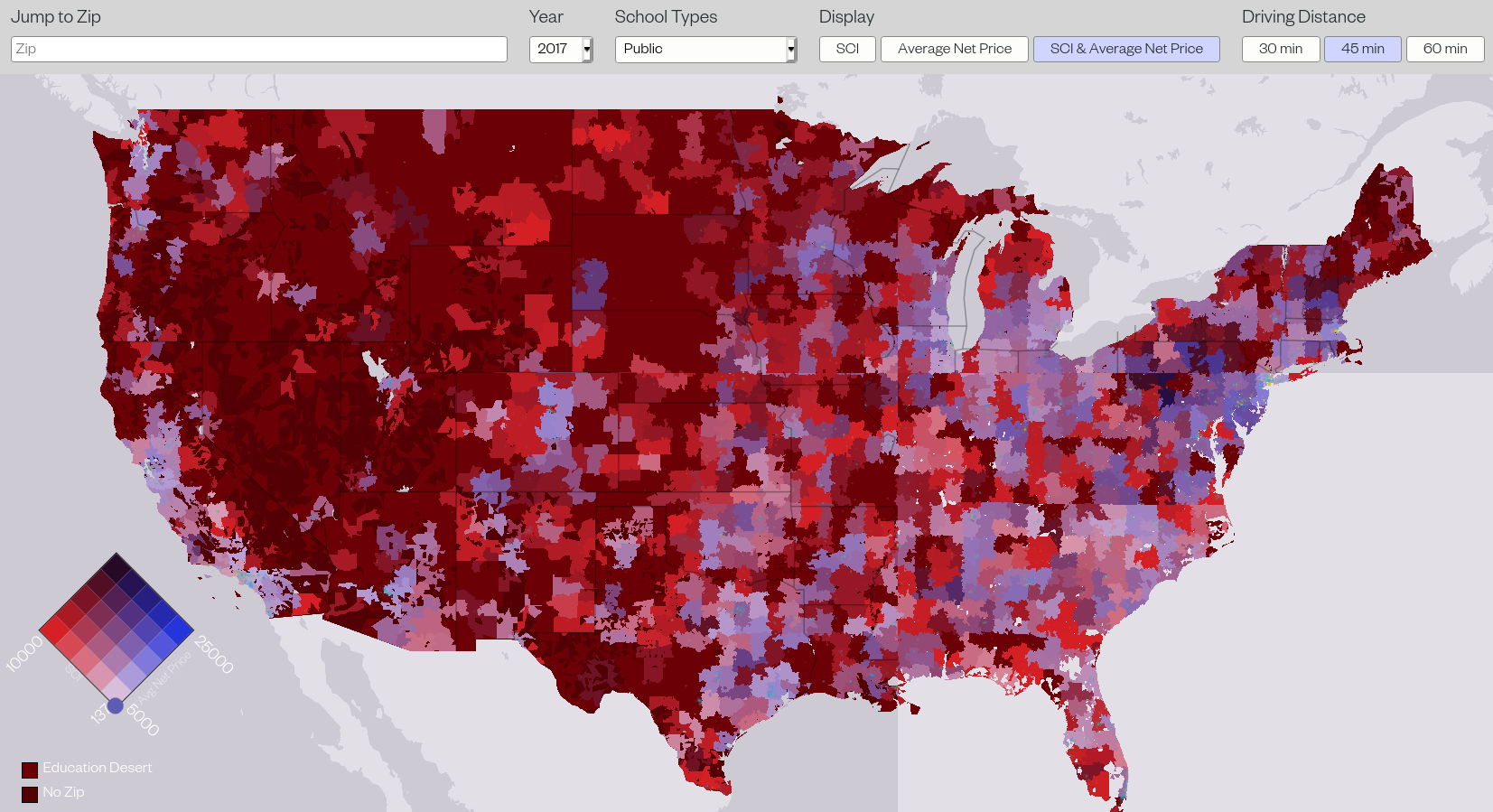

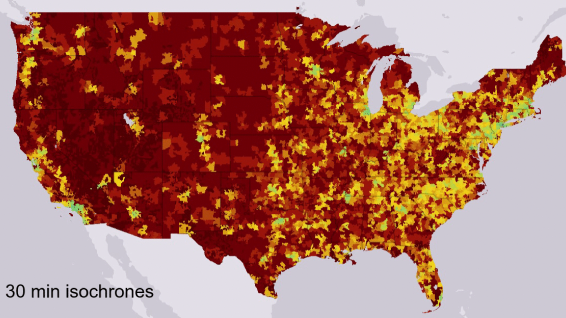

Forum on Education Deserts: Supporting Rural Regions With Fewer Colleges

On May 23, The Chronicle of Higher Education hosts a forum featuring JFI's Laura Beamer on higher education deserts in the...

Eduard Nilaj’s higher education analysis in Supreme Court amicus brief

Nilaj's work from Millennial Student Debt was cited by student loan experts.

Coverage of Millennial Student Debt

Marketwatch, Fortune, and Bloomberg covered our recent releases on the student debt crisis.

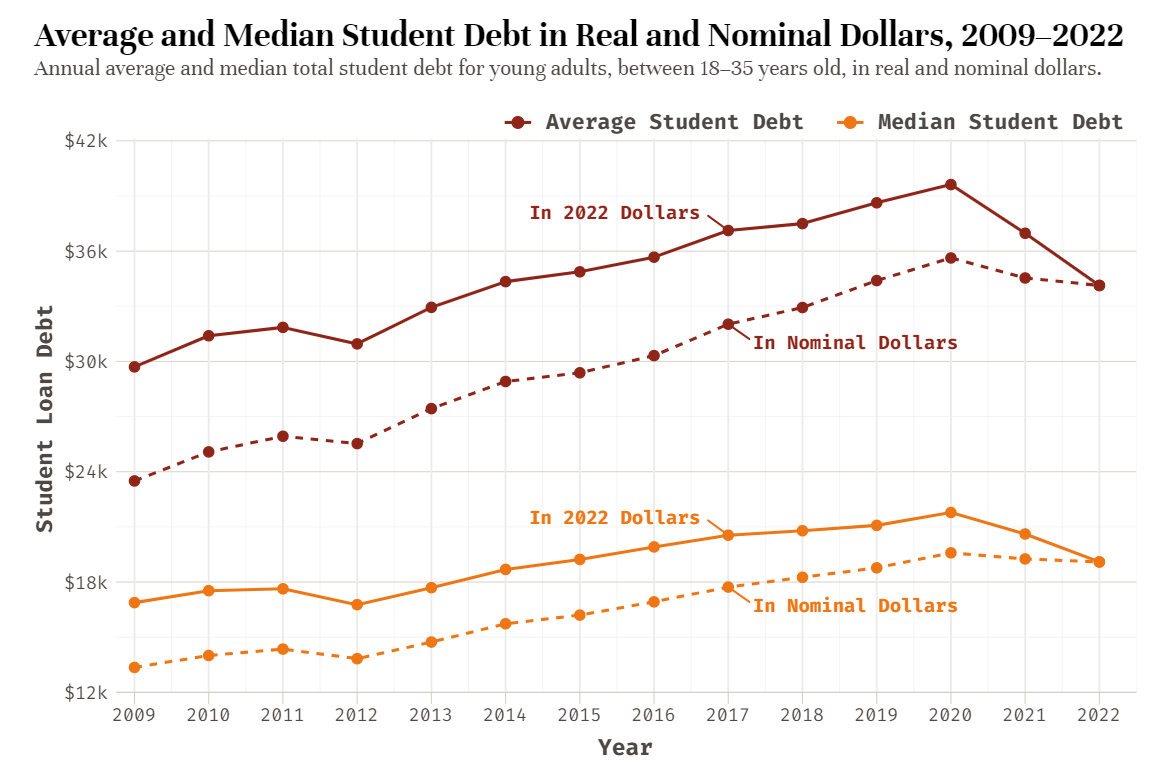

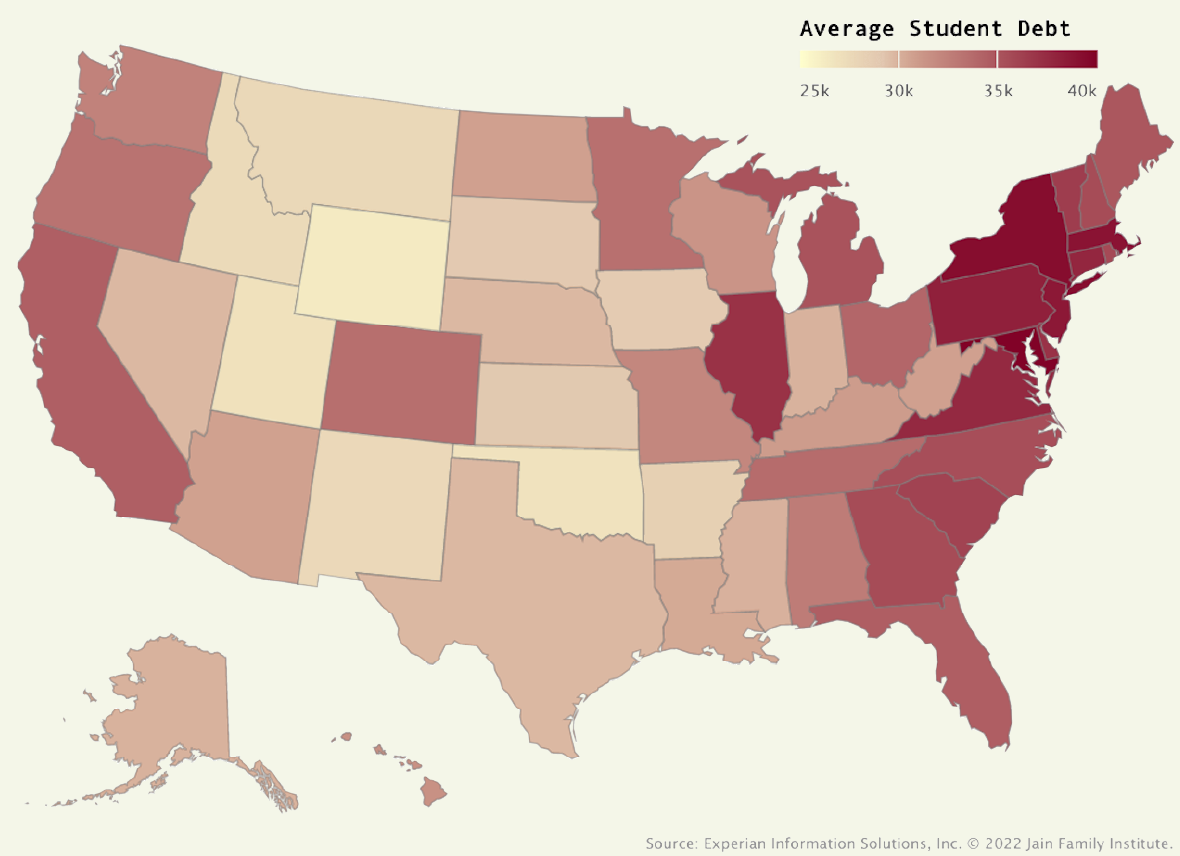

New Release: JFI’s Annual Student Debt Report, 2022

The 2022 "Student Debt and Young America" annual report shows a continued debt crisis but promising trends during three years of...

Student Debt and Young America in 2022 – Annual Report and Data Comparison Tool

The annual report provides a full analysis of the state of student debt in 2022—and what it could look like...

Part of the series Millennial Student Debt

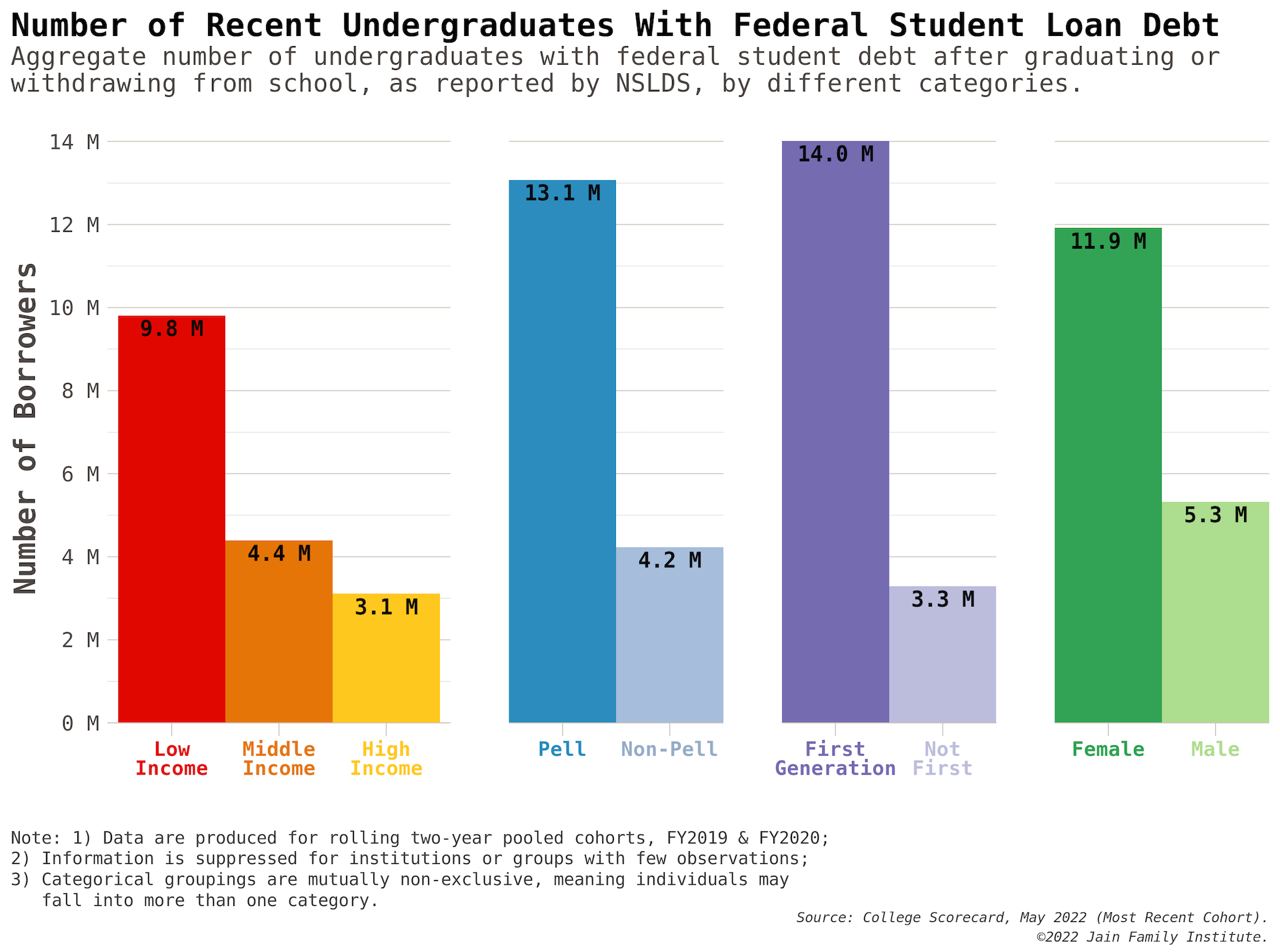

The Distribution of Student Debtors: Data, Narrative, and Debt Cancellation

The report analyzes demographic distributions of student debt burdens and repayment, providing a counterpoint to narratives that suggest the wealthy...

Part of the series Millennial Student Debt

New Student Debt Report Compares Debtor Makeup to Narratives on Debt Cancellation

The tenth installment in the ongoing Millennial Student Debt project, Laura Beamer's newest report combines three datasets to analyze debt...

Press coverage on JFI’s Higher Education Finance research

A roundup of recent coverage.

Research by Laura Beamer and Eduard Nilaj in the New York Times

JFI's higher ed research cited by David Brooks

Lead Researcher Laura Beamer on the Brian Lehrer Show

Beamer spoke about student debt cancellation

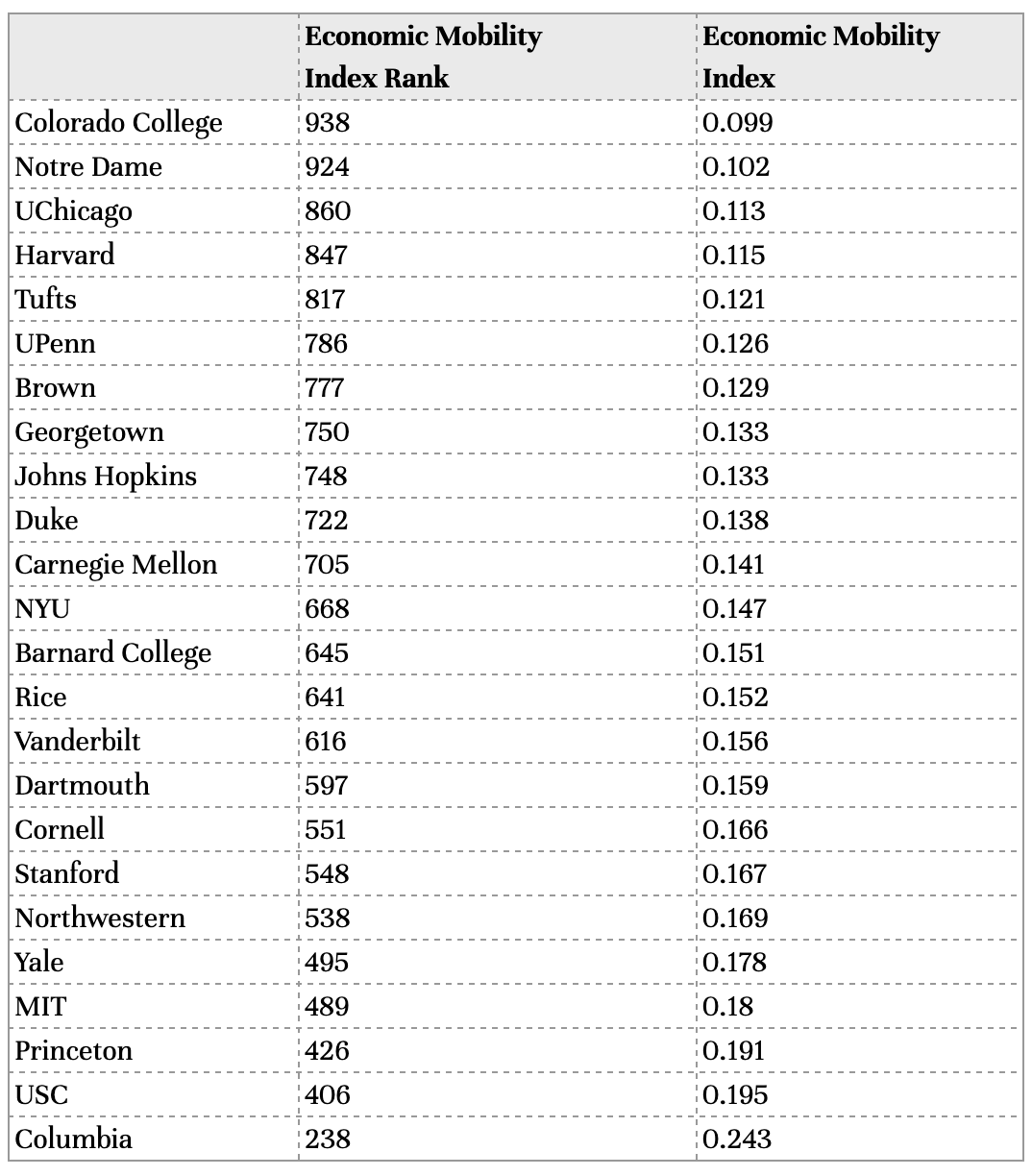

Cost Deception at Elite Private Colleges

Following Millennial Student Debt Part 7, "How Schools Lie: The Deceptive Financial Aid System at America's Colleges," Laura Beamer and Eduard...

Part of the series Millennial Student Debt